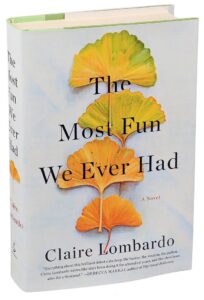

Claire Lombardo, whose debut novel “The Most Fun We Ever Had” follows a family shaken by secrets, talks about shifting from social work to fiction and how she wrote about what she doesn’t know.

It’s not every day you find a novel in which the grandparents can’t keep their hands off each other.

Claire Lombardo’s book debut, “The Most Fun We Ever Had,” out on Tuesday from Doubleday, is narrated by seven members of the Sorenson family. It is anchored by the four-decade marriage between David and Marilyn, “two people who emanated more love than it seemed like the universe would sanction.”

The story shifts backward and forward in time, following along as the couple raises four daughters, Wendy, Violet, Liza and Grace, in the Chicago suburbs. The return of Jonah, whom Violet put up for adoption after an unplanned pregnancy, unsettles the family, casting new light on decades of secrets and betrayals.

Lombardo, 30, spent about six years working for the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless, then spent a year in a social-work master’s program before dropping out to focus on writing. She graduated from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 2017 and still lives in Iowa City, where she teaches creative writing at the University of Iowa. We spoke by phone, and our conversation has been edited and condensed.

Tell me about the genesis of the book.

It began as a short story, something to keep me occupied when I was in social-work school. It originally started with Violet at the center — I wanted to explore a character with a perfect life that was upended by the arrival of someone she thought she’d never see again. But as I kept going, I was more interested by the satellite characters, especially her parents.

Did you draw on your own family life for inspiration?

I’m the youngest of five, and there’s a big gap in age between me and my siblings. They practically had a different set of parents than I did. I had the role of the little Switzerland. I’ve always been an observer, since I was a kid, and I do walk through the world in that way.

[ Read our review of “The Most Fun We Ever Had. ]

I’m always curious about people who come to writing after another career. How did you make that shift?

I took a break from my undergraduate degree and worked for the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless, first as an intern, then as a paralegal and the group’s intake person. I spent about six years there, working primarily with homeless parents and kids in the public-school system. That work made me more open-minded and a lot more aware of how nuanced and weird the world is.

You have to approach people from a place of zero judgment and complete empathy. It taught me how to interact with any number of people: Here I was, this young kid in her 20s from the Chicago suburbs, and all of a sudden I’m thrown into trying to help a mother of three with three jobs who didn’t know where her kids would sleep that night.

The transformative part about working with families at the coalition was that I had to separate my observation and writing brains, though I wasn’t really thinking of myself as a writer at that time.

It was a truly immersive experience. I loved it. It gave me a sense of purpose. It’s the same sense of purpose I feel as a writer.

How did social-work school figure into your development as a writer?

“A lot of young people feel like they don’t have stories to tell, or they’re not allowed to tell stories beyond their own experience,” said Lombardo, who teaches creative writing in Iowa. “I try to dispel that as much as I can.” Credit: Mary Mathis for The New York Times

As I was finishing my undergraduate degree at University of Illinois at Chicago, I was pretty set on applying for my masters in social work. I did have a creative writing professor pull me aside and tell me not to go, encouraging me to pursue writing instead. At the time I thought the idea of becoming a writer sounded ludicrous — actually, it still sounds ludicrous!

Once I got to social-work school, though, I was miserable. I lost my father very unexpectedly a few months in, and that really shifted my perspective and priorities. I became much more preoccupied with answering, “What am I doing and why?”

I have no memory of that year, to some degree. I got all As, I did my coursework, but working on the story in the evenings was therapeutic for me. Things were pretty dark, and it was an outlet for me, to immerse myself in a family that wasn’t my own.

How did your time at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop help?

I was lucky to find a community of supportive peers whose opinions I trusted. I arrived at Iowa with a very messy, 813-page draft, and my mentor, Ethan Canin, really helped with the structure of the book.

Having outside readers can show you how empathetically you’re rendering your characters. You have to have love for your characters and give them their due. And it was important for me to have readers who were parents, since I don’t have kids. I had to remind myself I’m allowed to write about things I don’t know, like a 40-year marriage. I just had to do my emotional homework.

Maybe most important was the fact that someone was paying me to write for the first time in my life. I had never just written or even been a full-time student. It was remarkable to have that freedom and to be told, “We trust you, go write a book.”

Now, as a creative writing teacher, what do you teach your students?

I work with both high-school students and undergraduates, and I love teaching, which I’m sort of surprised by! A lot of young people feel like they don’t have stories to tell, or they’re not allowed to tell stories beyond their own experience, and I try to dispel that as much as I can. As long as you know why you’re doing it and are writing with as much empathy as you can give, then I try to get them to write outside their comfort zone and explore points of view that are far from their own. Many of my students are studying engineering or business, and that exercise can be very freeing.

A lot of the work I do now is similar to what I was doing when I was at the Coalition for the Homeless: I helped them work through their own narratives and reframe their stories with power and purpose. I thought deeply about the ethics of storytelling — what’s mine to tell and what’s not. Perhaps I approached writing my own book with that sensibility.