Chicago Coalition to End Homelessness

City and census data indicate that 58,625 people experienced homelessness in Chicago throughout 2024, according to the most recent data available. Recent actions by the Trump administration have pushed an inhumane and racist agenda that criminalizes homelessness and spreads false information about its causes and solutions. These policies not only increase housing barriers and lead to more people becoming unhoused, but also put individuals experiencing homelessness at even greater risk than they already are. We are also concerned that the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) fails to recognize all of the ways that people experience homelessness. As a result, HUD-funded services are often unable to reach everyone in need and fall short in both the scale and the type of support provided.

For the past ten years, Chicago Coalition to End Homelessness has produced annual estimates that reflect the full scope of homelessness beyond what official counts may capture. In this report, we present this data in context and answer common questions about the realities, causes, and solutions to homelessness.

Quick Links

Contrary to the narrative behind recent federal action, homelessness is a systemic failing rather than an individual failing. This report emphasizes that ending homelessness requires increased funding and policy change, and it explores what YOU can do to join the fight.

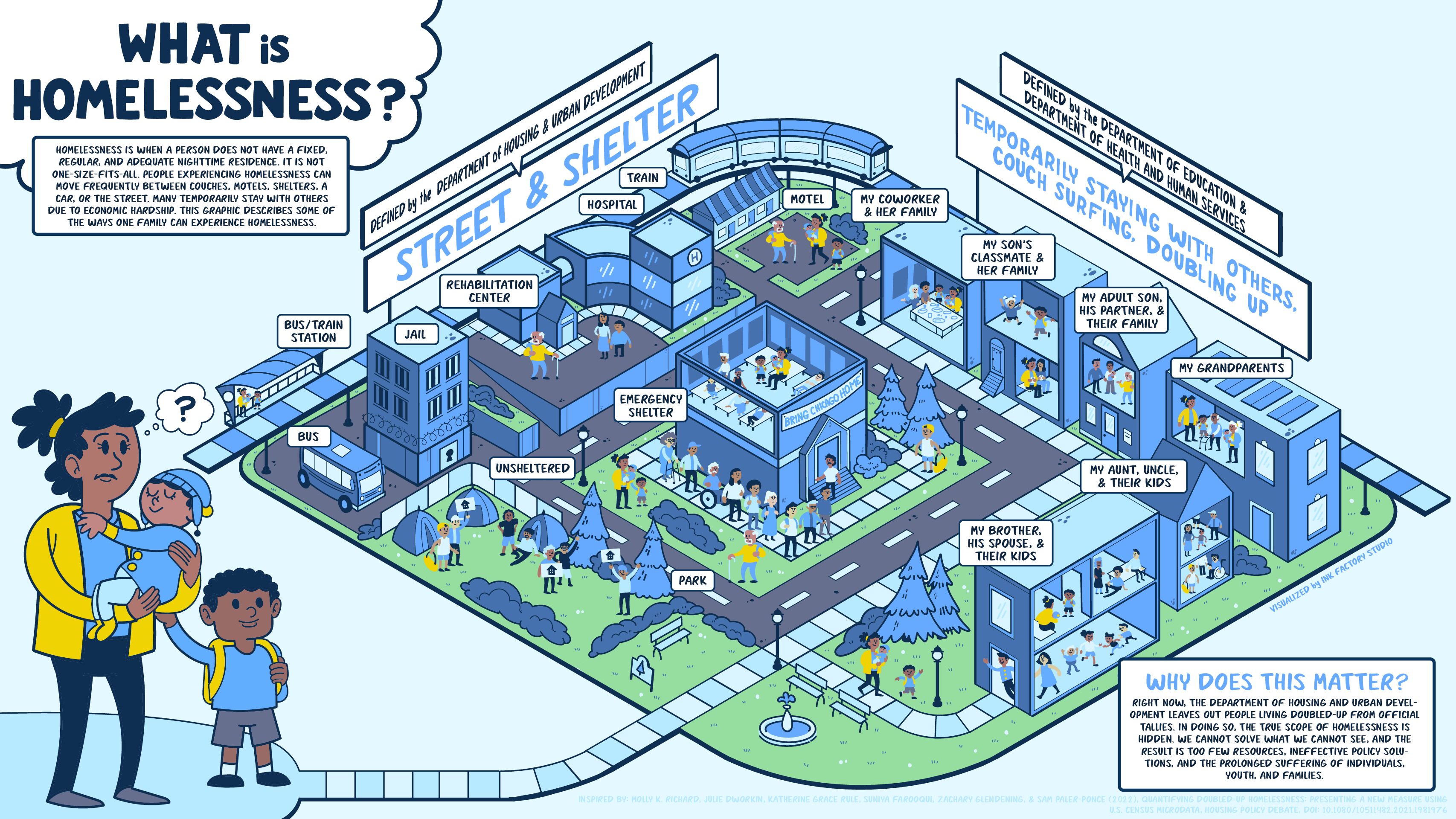

I thought homelessness just meant someone sleeping outside, like on a park bench.

What is homelessness

actually?

Homelessness is any situation where someone does not have a fixed, regular, and adequate place to live. This can mean sleeping outside, in a shelter, in a car, on someone’s couch, or other impermanent or overcrowded situations. A single person often experiences several of these forms over time.

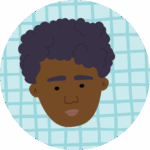

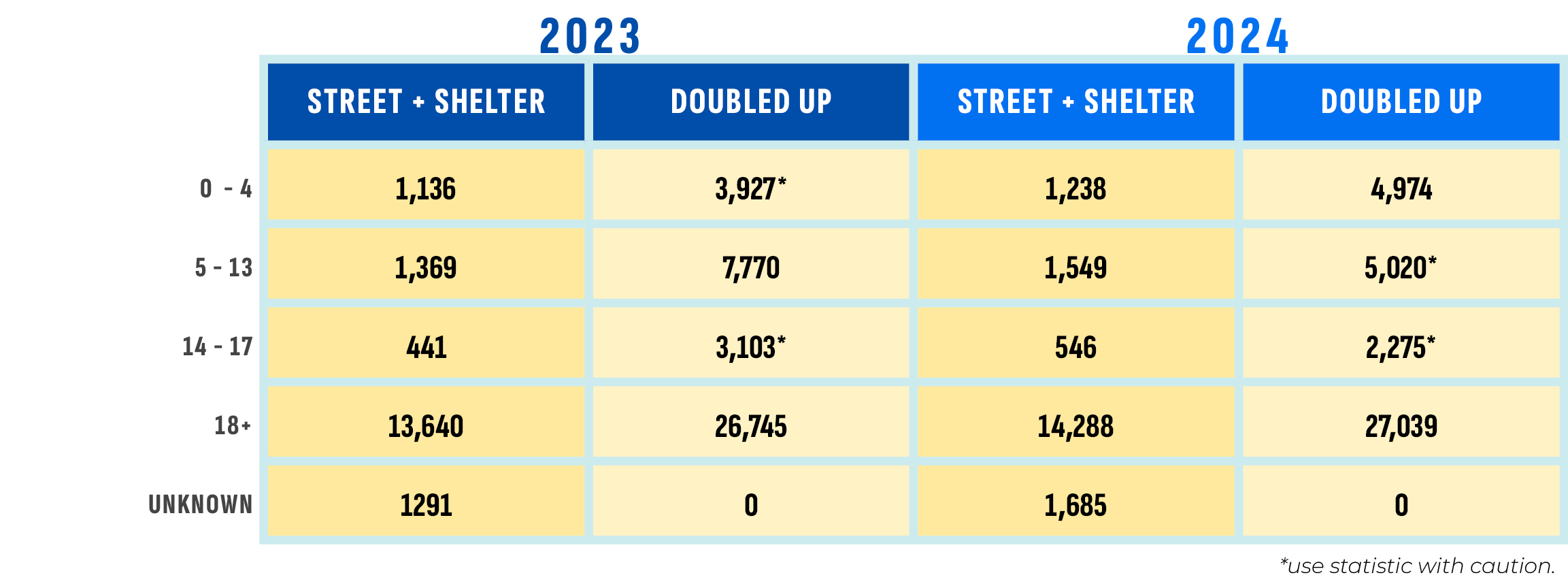

HUD, however, defines homelessness more narrowly—mainly as living in shelters, on the street, in places not meant for habitation, or fleeing domestic violence. In Chicago, the most common experience is “doubling up,” when someone stays with friends or relatives because they have nowhere else to go (see graphs). Other entities of the Federal Government, such as the Department of Education do recognize doubling up as homelessness, but they do not provide housing resources.

I thought only 18,836 people were experiencing homelessness in Chicago in 2024.

Where did that number come from?

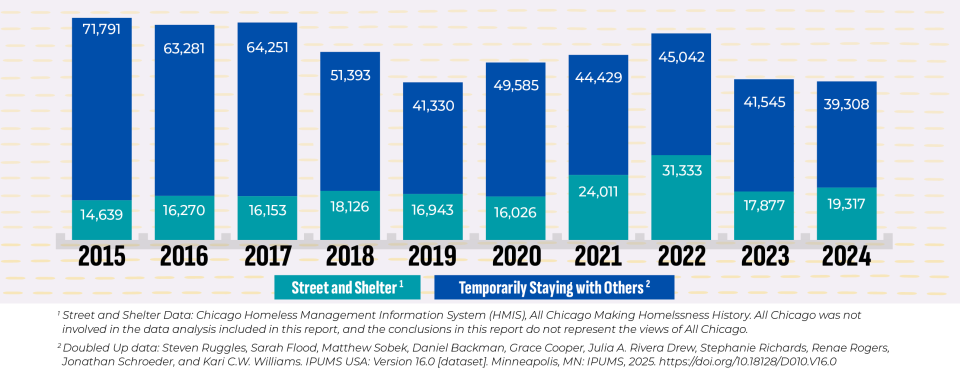

That figure comes from the Point-in-Time (PIT), HUD’s traditional method for estimating homelessness. It only counts people staying in a shelter or visibly on the street. The PIT is limited because it leaves out many groups, like people who are doubled up with friends or family. Additionally, it’s just a snapshot from one night each year, usually a cold night in January.

Year to Year, Street/Shelter & Doubled Up

Year to Year, Accessed Services vs. PIT

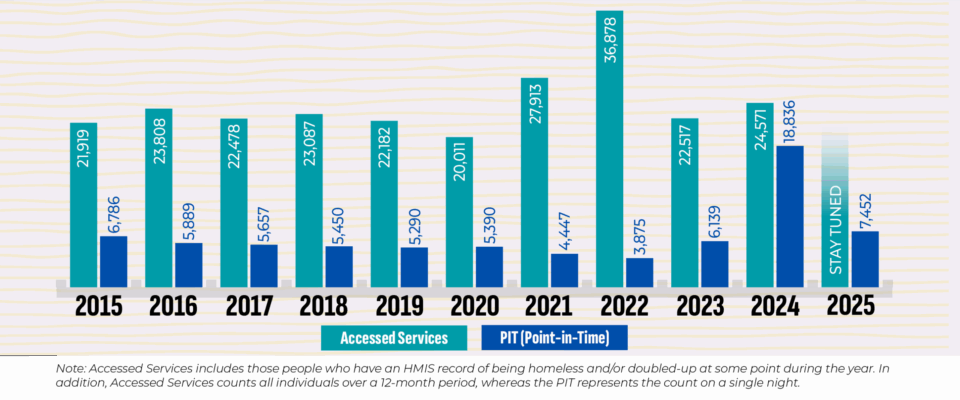

Homelessness by Family/Household Type

COUPLED PARENT = Parent in two-parent family units with children under 25

CHILD OF COUPLED PARENTS = Individual under 25 who is with their coupled parents

SINGLE PARENT = Family with one parent and children or offspring under 25

CHILD OF SINGLE PARENT = Individual under 25 who is with their single parent or guardian

ADULTS ONLY = Household/family unit with no minors

SINGLE ADULT = Individual 25 or older with no other household members

UNACCOMPANIED YOUTH = Individual under 25 with no other household members

25+ HOH = Members of family or household units with at least one adult head of household (25 or older) and members under 25

25+ ONLY = Members of household units of adults only (all 25 or older)

SINGLE 25+ = People 25 or older with no other household members

SINGLE (UNDER 25) = People younger than 25 with no other household members

UNDER 25 HOH = Members of family or household units with no adults (25 or older) with or without dependents

Race & Ethnic Demographics:

Age Ranges:

The numbers have changed over the past 10 years.

What kinds of policy and other things might have caused that?

This timeline shows the total estimate over the last 10 years and things that may have impacted it.

The causes of homelessness and the policies impacting it are complex and interact in complicated ways. We focus mostly on policy here because policy is made by people and can be changed by people. It is important to note that although we have tried to be comprehensive in this report, there are factors that we may not have fully addressed.

The estimate of 58,625 suggests that homelessness has been declining in Chicago.

What could be causing the decline?

We think there are two main reasons behind the decrease. First, COVID relief funds provided temporary support that helped people stay housed, but those resources weren’t permanent, so this trend may reverse. Second, rising costs in Chicago have pushed many residents to leave the city, particularly low-income Black Chicagoans, which lowers the local count but doesn’t necessarily mean fewer people are experiencing homelessness overall.

This decrease does indicate that increases in resources directed at housing services, such as those due to COVID and homelessness services based in Housing First have the power to help end homelessness. Unfortunately, under the Trump administration the Department of Housing and Urban Development attempted to reduce funding to both homelessness services and Housing First policies. These changes may lead to a loss of any progress that has been made in ending and preventing homelessness.

I always heard that homelessness was caused mostly by individual problems, like substance use. But if that were true, the rates of homelessness wouldn’t vary so much by year or by city.

So what actually causes homelessness?

Homelessness is driven by policy, economic, and community inequities—not just individual circumstances. In Chicago, for example, Black residents make up just under 30% of the population but over 50% of people experiencing homelessness.

The primary root cause is systemic racism, which shapes housing, employment, and the criminal legal system. Discriminatory practices like redlining blocked Black families and other communities of color from homeownership and wealth-building. Racism also contributes to disproportionate incarceration, which directly increases the risk of homelessness. Overall, racial discrimination creates lasting barriers that keep communities from securing stable housing.

Overlapping with racism are inequities in health and disability. For example, people who rely on Supplemental Security Income (SSI) face a difficult tradeoff: they must remain unable to work in order to qualify, yet the benefit amount is far too low to cover housing costs. In addition, people with disabilities or chronic health conditions are at greater risk of becoming homeless, and once homeless, their conditions often worsen due to lack of stable shelter, consistent care, and safe environments.

Similarly, while substance use is not the primary cause of homelessness, people already vulnerable due to systemic inequities may be more likely to become unhoused if they use substances. More importantly, the trauma of homelessness itself increases the risk of substance misuse and creates barriers to accessing care. This cycle reflects broader policy failures, including the federal response to the opioid epidemic.

Furthermore, sexual and gender-based violence is both a pathway into homelessness and a barrier to securing stable housing. People who identify as Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Queer, or other associated identities not only experience higher rates of homelessness but also face greater risks of violence and discrimination while unhoused.

These impacts of racism, sexism, ableism, and homophobia all intersect with the broader housing affordability crisis. There is simply not enough affordable housing to meet the need in Chicago or nationwide, and restrictive policies have limited alternative housing options. Importantly, the crisis is not due to a lack of housing stock—Chicago had 109,793 vacant housing units in 2024, nearly twice the number of people experiencing homelessness.

There are many complex and intersecting reasons why people experience homelessness. Framing it as an individual problem distracts from the systemic and policy changes that are necessary to actually end homelessness.

Homelessness is driven by policy, economic, and community inequities — not just individual circumstances.

Framing homelessness as an individual problem distracts from the systemic and policy changes that are necessary to actually end homelessness.

I don’t know… it seems like if people just got a job, they could get housing, right?

It’s not that simple. Many people experiencing homelessness are already employed, but wages often aren’t enough to cover the high cost of rent. For those who are unemployed, homelessness and unemployment reinforce each other, making it harder to get either stable work or housing. These barriers are even greater for Black people and other communities of color because of systemic discrimination in both the labor and housing markets.

If people can’t afford housing, why don’t they just stay with friends or family?

Many people do, but those situations are often unstable or unsafe, and not everyone has a social network that can offer housing. Even when someone does have a temporary place to stay, doubling up can disqualify them from many housing services. So, while it may seem like a solution, doubling up is often dangerous, impractical, and still a form of homelessness.

So, what help is out there for people trying to get housing?

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is the primary federal funder of housing and supportive services. HUD organizes these programs through a system called the “Continuum of Care” (CoC), which coordinates housing resources within a region. As is, the homelessness response system does not have enough funding, and not everyone experiencing homelessness qualifies for help. Even for those who are eligible, strict documentation requirements, complicated prioritization rules, and other barriers often prevent people from actually getting into housing.

Though imperfect, it is important to note that the CoC system is under threat by the Trump administration. Ending the CoC system without an adequate replacement would cause hundreds of thousands of people to return to homelessness.

Housing programs funded by the State of Illinois and the City of Chicago generally operate through the CoC system and face the same barriers around access and limited resources. To address the gap, CCH and its partners launched the Bring Chicago Home campaign in 2018 with the goal of securing more stable local funding.

The bottom line is that no single service, benefit, or organization can solve homelessness on its own.

The bottom line is that no single service, benefit, or organization can solve homelessness on its own.

Homelessness sounds really complicated, and it seems lots of things have already been tried.

What can actually be done to end it?

Policy has the power to both prevent and end homelessness, but only if it is comprehensive, accessible, and ensures adequate affordable housing for all. Effective policy must also confront the discriminatory root causes of homelessness, including racism, homophobia, and ableism. This can be achieved by not only allocating more funding to homelessness policies, but also by ensuring that resources are efficient, low-barrier, and flexible.

Proven approaches like the “Housing First” model are now being dismantled by the Trump administration, replaced with new policy guided by executive orders that will criminalize and worsen homelessness. Homelessness persists not because it is inevitable or unsolvable, but because of harmful policies like those of the Trump administration.

Blaming individuals for their own poverty distracts attention from broken housing markets and underfunded support programs while overlooking proven solutions like Housing First and accessible housing policies, which have effectively reduced homelessness. Punishing people for experiencing homelessness does not solve homelessness, it simply hides homelessness and makes it harder for people to escape.

Everyone experiencing homelessness deserves access to immediate stable housing.

Effective policy can make this a reality.

Policy has the power to both prevent and end homelessness, but only if it is comprehensive, accessible, and ensures adequate affordable housing for all.

Everyone experiencing homelessness deserves access to immediate stable housing.

Effective policy can make this a reality.

Methodology

How do you come up with your annual estimate of people experiencing homelessness in Chicago?

To get a better understanding of the number of people experiencing all types of homelessness, Chicago Coalition to End Homelessness (CCH) created a new method. CCH worked with researchers from Vanderbilt University and the Social IMPACT Research Center of Heartland Alliance to create this new way of estimating homelessness. This method is published in the Housing Policy Debate journal and the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series dataset is open to anyone to view and use for their own research. This estimate aims to not count the same person twice by removing duplicate entries whenever possible. Given the limits of all the data sources, there may still be some duplicates within the data. In 2024, CCH found that 5,254 people in the Homelessness Management Information System (HMIS) used homeless services and stayed with friends or family at some point during the year. CCH removes this population from the street and shelter estimate, assuming that they would be captured in the doubled-up estimate.

Who is included in Homeless Management Information System (HMIS) data?

To count people experiencing street and shelter homelessness throughout the year, CCH asked for a count of everyone who accesses certain types of services recorded in the Homeless Management Information System (HMIS). The Department of Housing and Urban Development defines homelessness as people living in places not meant for habitation, emergency shelters, or transitional housing. The HMIS data includes all people served, anytime during the specified time period, by one or more of these project types: Emergency Shelter, Street Outreach, Safe Haven, Transitional Housing, and Coordinated Entry.

In addition, if a person can be identified as having doubled up in the past year, that person is excluded from the HMIS data. While this report refers to all HMIS data as “street and shelter homeless,” some people enrolled in the Transitional Housing and Coordinated Entry project types meet other categories of homelessness, if those people were unable to be excluded from the HMIS data.

The data also excludes people who were served exclusively by enrollment in a Rapid Re-Housing program. Although temporary, Rapid Re-Housing programs are considered permanent housing by HUD and by the Chicago Continuum of Care. These estimates do not include people who are experiencing street-based homelessness but have not used homeless services. It also does not include people who are homeless but may not want anyone to know, like those who do sex work and cannot safely report their income. This does not include people who were in jail the entire year and were experiencing homelessness before they entered the carceral system. Finally, people who were in healthcare institutions the entire year are also not included.

Source: Chicago Homeless Management Information System (HMIS), All Chicago Making Homelessness History. All Chicago was not involved in the data analysis included in this report, and the conclusions in this report do not represent the views of All Chicago.

In your analysis how does CCH define “Homeless by Temporary Staying with Others?”

For our analysis “temporarily staying with others” includes poor individuals and families who fall outside of the conventional household composition and cannot afford to live in housing of their own or formally contribute to housing costs. For the purposes of this estimate, individuals who meet the following conditions are considered homeless:

- Adult children and children-in-law of the household head who have children of their own, are married, or are single but live in an overcrowded (more than two people per bedroom) situation.

- Minor and adult grandchildren of the household head, excluding:

- Minor grandchildren of the household head when the household head claims responsibility for their needs.

- Minor grandchildren whose single parent is living at home and is under 18 (i.e., children of teenage dependents).

- Other relatives of the household head: Parents/parents-in-law, siblings/siblings-in-law, cousins, aunts/uncles, and other unspecified relatives of the household head who are under the age of 65, excluding:

- Minor siblings of the household head when the minor’s parent is not present (so the household head may assume responsibility for minor siblings).

- Single and childless adult siblings of the household head, when the household head is also single with no children—resembling a roommate situation.

- Parents/parents-in-law, siblings/siblings-in-law, cousins, aunts/uncles, and other unspecified relatives of the household head who are over age 65 and in an overcrowded situation.

- Non-relatives of the household head such as friends, visitors, and “other” non-relatives, excluding:

- Roommates/housemates, roomers/boarders, and unmarried partners or their children.

Got it. So the solution to homelessness is effective policy, not criminalization or institutionalization. All of that sounds like something only policymakers can do.

What can I do to help end homelessness?

It’s important to recognize that we, the people of the United States of America, Illinois, and Chicago are policymakers, and we do have the power to make change. Here are some specific things you can do:

-

Take action with the Chicago Coalition to End Homelessness.

-

Support CCH’s local advocacy and other campaigns to effectively address homelessness. Sign up here to stay connected.

-

Follow and support local initiatives like these:

-

Engage in the Chicago city budgeting process. Sign up here to stay connected.

-

Know your Chicago Alderperson and other representatives, and contact them about homelessness policy.

-

Advocate against local policies that criminalize people experiencing homelessness.

-

Check out the National Coalition for the Homeless’ list of accessible, everyday actions.

-

Treat your unhoused neighbors with respect by greeting them, making eye contact, and acknowledging their humanity. Communities that support people experiencing homelessness are healthier, safer, and stronger overall.

-

Share this report!