The Wilson viaduct. Photo: John Greenfield

By John Greenfield

Did you ever notice how the glass panels of standard CTA bus shelters don’t go all the way to the roof, so that when you wait for a ride during a heavy rainstorm you tend to get wet anyway? Have you used a public bench that was sort of uncomfortable because city planners wanted to make sure it would be almost impossible to sleep on? Ever notice that urban bridges often have large boulders placed underneath them to create an uneven surface, or how window frames sometimes feature spiky fixtures to keep people from sitting on them? That’s called defensive architecture, strategies to discourage loitering, which often have the effect of making public space less useable and welcoming for all of us.

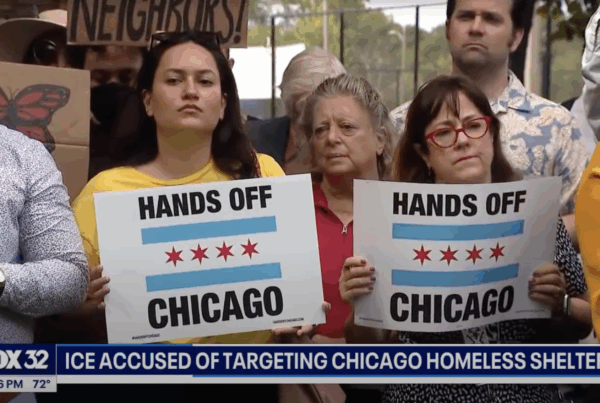

It appears that the city of Chicago wants to use bicycle infrastructure as a form of defensive architecture, by installing bike lanes on the wide sidewalks in Lake Shore Drive’s Lawrence and Wilson viaducts in Uptown. For years people experiencing homelessness have camped out on the sidewalks within the underpasses, many of them using tents provided by homeless advocates. On occasion the city has forced these folks to remove their belongings, such as before a 2015 Mumford & Sons concert at nearby Montrose Beach, which has often resulted in protests by advocates and threats of lawsuits. The situation has been a constant headache for city officials, especially bike-friendly local alderman James Cappleman.

To varying degrees, I’m sympathetic to all involved parties. It’s generally not lawful to camp out in public space in Chicago, and it’s understandable that some of Cappleman’s constituents don’t feel they should have to pass through an illegal homeless encampment in order to walk to the beach.

On the other hand, these tent cities provide the residents with shelter from the elements, safety in numbers, and a sense of community. These locations make it easy for them to be located by people who wish to offer donations of goods and services and check on their wellbeing. Moreover, the encampments are a high-profile symbol of our city’s failure to adequately address its homelessness problem, which is one reason they’re so embarrassing for politicians.

As reported by the Sun-Times’ Mark Brown, the city is planning to install bike lanes on the sidewalks of the viaducts as part of the reconstruction of the underpasses, which is slated to begin next month. Presumably the new bikeways will be similar to the sidewalk lanes in a Metra viaduct on Randolph between Canal and Clinton in the West Loop.

While there’s no question that the crumbling Lawrence and Wilson underpasses should be rebuilt, the bike lanes would make it impossible for homeless people to return to the viaducts after the renovations are finished. Therefore on Wednesday the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless announced its intention of suing the city if it follows through with the bike lane plans. In a letter to city officials, the group demanded that permanent housing be found for all people currently living in the underpasses, and that the project be redesigned so that there will be space for tents in the future. There was a protest over the issue yesterday.

When I checked in with Chicago Department of Transportation spokesman Mike Claffey about the bike lane plans today, he provided the following statement:

The improved viaduct will better accommodate the high volume of pedestrians, bicyclists and vehicles that travel to and from the lakefront more safely, including improved sidewalks and dedicated off-street bicycle paths. Designs are final and a contractor has been selected for the work. Construction work is expected to start in September and is estimated to take eight months.

When developing and designing projects such as the Lawrence and Wilson viaducts, CDOT makes a determination about layout based on traffic volume, conditions on nearby roadways and longer-term development plans in the adjacent communities. Each project is different and what works for one viaduct may not be the best design for others. In this case, CDOT began the design process by incorporating the recommendations in the Streets for Cycling Plan 2020, which was published in December 2012. Lawrence Ave. from Austin to the Lakefront Trail is included as a crosstown bike route. Wilson from Spaulding to the Lakefront Trail is designated a neighborhood bike route.

[It was determined that], given the available right of way, built environment, and traffic volumes, the best option would be to utilize the unusually wide right of way for separated bike lanes and pedestrian ways, while preserving traffic capacity. This is consistent with other repairs and building of bridges along Lake Shore Drive, with an upgraded pedestrian/bicycle bridge at North Avenue and ongoing work on the Navy Pier Flyover. New pedestrian/bicycle bridges are also being added to the south side, at 35th St. (finished in 2016) and 41st St., currently under construction.

While, all other things being equal, putting bike lanes on these sidewalks would be a good strategy to make biking through these tunnels somewhat more comfortable, as things stand these are not particularly hazardous passages for cyclists. Under the current configuration, tents included, families and less-confident riders can already ride slowly or walk their bikes on the wide sidewalks within the viaducts. As an Uptown resident myself, my experience has been that the folks living in the viaducts are friendly to passers-by and careful to leave plenty of room on the wide sidewalk for pedestrians.

Moreover, there are hundreds of viaducts in this city. If it’s simply a coincidence that the two underpasses where tent cities are causing a public relations nightmare for the city are the ones that are getting bikeways that will displace those encampments, as CDOT claims, that’s a heck of a coincidence.

More likely, this is a very intentional attempt by the city to use bike infrastructure as defensive architecture, to try to keep the homeless from occupying public space in the future. Other bike advocates may disagree with me on this issue, but in this case I say “Not in my name.”