By Odette Yousef

Homeless couple Shawn Moore and Amie Smith said city workers have thrown out more than a dozen of their tents in the past two years. Yet, they said they still don’t understand where they can — and can’t — pitch a tent in Chicago and why.

The couple said they first tried to set up tents on the sidewalks of lower-level streets downtown near Millennium Park, but police regularly rousted them from those locations. So they searched for an even more secluded spot and eventually found a small patch of concrete a few blocks east.

The new spot, just off Lake Shore Drive near Randolph Street, offered a variety of benefits. They said the highway overhead protected their belongings from the rain. And because the spot is not a sidewalk, they were not obstructing pedestrians. Best of all, they said, was the magnificent view of Lake Michigan.

Moore said that two weeks after they settled in, police discovered their new location and came by every day in an effort to get them to move — again. Now, the couple said, city workers take their tents at least once a month. To prevent their belongings from ending up in the back of a garbage truck, they said one person has to be there at all times, which is time not spent on things like searching for a job.

“[You’re] not going to find many places that’s not actually in somebody’s way,” Moore said. “We’ve been fortunate enough to find a couple, but I’m sure it’s not going to be many more if they run us off of this one.”

Moore and Smith aren’t alone. Residents who lack stable housing pitch tents throughout the city. But those tents, which offer freedom and privacy not found in homeless shelters, also put them in the crosshairs of city workers. Lawyers for homeless people said the city’s rules on tents are vague and the enforcement is uneven.

Why live in tents?

Chicago had 5,657 homeless people in early 2017, according to a city report on homelessness. City officials and homeless advocates said they don’t know how many of those people are setting up tents as makeshift shelters. But the city report, which some advocates believe drastically undercounts the homeless population, found 1,561 people living in places not meant for human habitation, such as on sidewalks or in parks.

In April, Department of Family and Social Services deputy commissioner Alisa Rodriguez said the city does not have enough space at shelters for all the known homeless people. The acknowledgement came during a hearing about a proposed tent city in front of a shuttered elementary school in the Uptown community.

That means city officials acknowledged that some people may have little choice but to live outside because of capacity limits at shelters and a deficit of affordable housing. As seen throughout Chicago, some of them live in tents.

The municipal code says the city can limit tent use

So where can homeless Chicagoans pitch a tent? One thing city officials point to is a provision in the city’s municipal code.

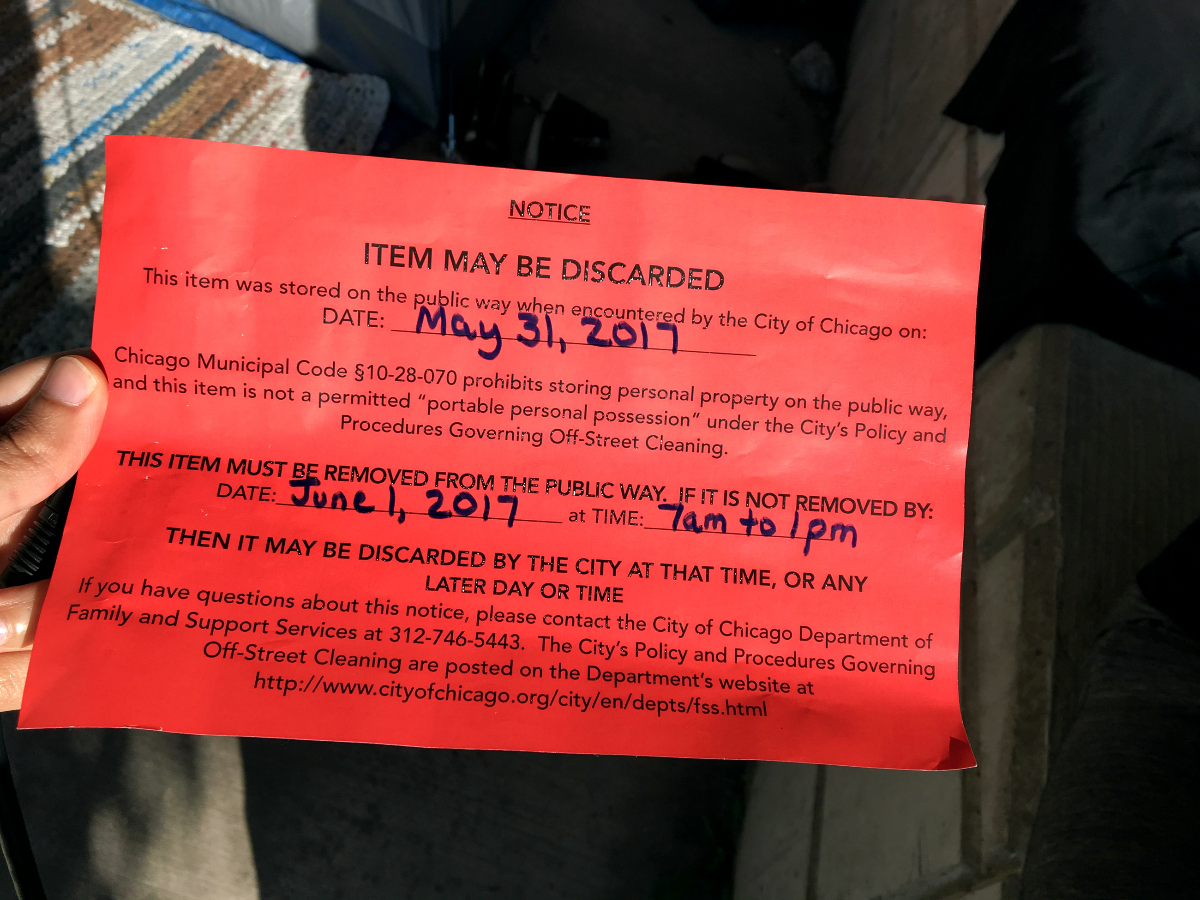

According to the code: “No person shall use any public way for the storage of personal property, goods, wares or merchandise of any kind. Nor shall any person place or cause to be placed in or upon any public way, any barrel, box, hogshead, crate, package or other obstruction of any kind, or permit the same to remain thereon longer than is necessary to convey such article to or from the premises abutting on such sidewalk.”

The code doesn’t specifically mention tents, but city officials indicated the spirit of the rule is not to obstruct the sidewalk.

Jennifer Rottner, a spokeswoman for the city’s Department of Family and Social Services, added that some exceptions may be made for tents, but only if the city grants permission.

“While all residents are welcome to use the public way, they do not have the right to obstruct the public way or keep tents or structures on the public way without a permit,” Rottner wrote in an email to WBEZ.

But Rottner did not know what type of permit was required or how to apply for it.

While city officials cite municipal code, Illinois also has one of the strongest laws in the country when it comes to protecting the rights of homeless people. The Illinois Bill of Rights for the Homeless Act, passed in 2013, affirms that Illinois residents may not be treated any differently simply because they don’t have a home.

Matthew Piers, an attorney with Hughes Socol Piers Resnick & Dym who is helping represent Moore and Smith, said the Illinois Bill of Rights for the Homeless Act and the municipal code together mean the city can impose some restrictions on tents — like limiting what times they can be up — but don’t allow the prohibition of tents outright.

“Certainly the city couldn’t validly say you couldn’t pitch a tent in your backyard,” Piers said. “As long as they’re not blocking the public way, or creating a nuisance or even inconvenience to anybody else, I would seriously question any attempt to limit their use of tents.”

Moore and Smith’s noted that their tent overlooking the lake was not on a sidewalk.

Two police officers told WBEZ a third reason for taking the couple’s tent in July. They said tents were not allowed in the central business district. Anthony Guglielmi, spokesman for the police department, referred questions about the officers’ claim to the city’s Law Department and Department of Family and Social Services.

Bill McCaffrey, a spokesman for the Law Department, said no such law exists.

The city says it takes tents because of a non-binding agreement

City officials cite another basis for removing tents, a legal settlement called the Bryant Agreement.

The city reached the settlement with 16 homeless people in 2015. The agreement spells out how the city will conduct cleanings of sidewalk areas where homeless people live. It also lists what — and how many — personal possessions homeless people can keep with them.

McCaffrey, the Law Department spokesman, pointed to the agreement when asked about where homeless people can have tents in the city. In an email, he rattled off a list of items prohibited under the agreement: “Tents, non-air mattresses, box springs, potted plants, crates, large appliance boxes, carts, gurneys, wagons or furniture, including chairs, tables, couches and bed frames.”

However, McCaffrey’s list differs from what’s written in the agreement, which makes no specific mention of tents. McCaffrey did not respond to follow-up questions about why his language differed from that in the agreement or whether the off-street cleaning policies have changed.

Piers, the attorney, noted that the Homeless Bill of Rights has higher standing than the Bryant Agreement.

“[The Bryant Agreement] has no binding effect on any other person other than the signatories to the agreement,” Piers said. “And, by the way, at the city’s insistence it has no binding effect to the City of Chicago.”

For homeless people, the patchwork is confusing

Many homeless residents, like Moore and Smith, said the real problem is how to make sense of the city’s selective enforcement of its tent rules.

Moore and Smith said they regularly had their tents taken away from them when they were in areas that pedestrians do not frequent, such as lower-level streets downtown or highway exit ramps. By contrast, the city tolerated — often contentiously — dozens of tents on sidewalks that pedestrians regularly use at the Wilson and Lawrence Avenue viaducts in Uptown. The Uptown tent cities were eventually forced to disband in September, but only because of construction on the overpasses.

Diane O’Connell, an attorney with the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless helping Moore and Smith, said she has concluded that the city aggressively removes tents when media aren’t looking. She noted the city backed down from removing tents in Uptown in 2016 after numerous news reports highlighted the difficulties those homeless residents would face going into the winter.

Neither Rottner nor McCaffrey answered a question about claims that the city enforces tent rules selectively.

Piers said the city’s uneven enforcement underscores a need for clear and binding rules.

Moore said he also needs clarity on another issue, namely why the city is allowed to seize their belongings. The Illinois Bill of Rights for the Homeless allows him the same security in his personal possessions as anyone with a home might expect.

“You can keep telling me to take it down, take it down, take it down,” Moore said. “But why do you have the right to keep taking it? That’s what I’m not understanding…. I purchased this. It’s not illegal for me to purchase. It’s not illegal for me to have. It’s not illegal for me to put up. Why do you keep taking it?”